2/27/23, 4:04 PM Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language - WSJ

By Cameron McWhirter | Photography by Susannah Kay

WHITTIER, N.C.—In a cozy house in a bucolic valley, a handful of students gather weekly to learn how to speak the language of their Cherokee ancestors.

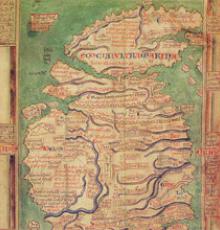

The Cherokee people once occupied a large swath of the southeast U.S.

Most Cherokee, as well as neighboring tribes, were forcibly relocated by the federal government in the 1830s to what is now Oklahoma, an event known as “the Trail of Tears.” Some Cherokee avoided or escaped the removal and stayed in North Carolina, forming the basis for what is today the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation, a federally recognized tribe.

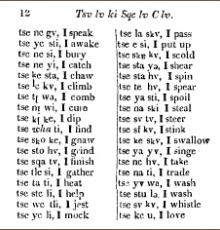

But only 200 or so people are fluent now around the mountain town of Cherokee, N.C., out of the roughly 14,000 Cherokee who live in the area. “We’ve somehow got to learn some of it, because it’s part of who we are,” said student Louise Taylor Goings, 68 years old, who remembers hearing her parents speak to each other in Cherokee when she was little.

Now, Ms. Goings is trying to help the language survive for her grandchildren. She and the other students hope to master the native tongue by using new tools to parse the grammatical structure of Cherokee, a notoriously complex language.

“One big problem for teaching the language is that no one has developed an accepted curriculum. ... Cherokee doesn’t have any of that”.

— Brad Montgomery-Anderson

As many as half of the world’s 6,000 or more languages could disappear by the end of this century as a result of globalization and the spread of dominant languages such as Chinese, Spanish, English and Arabic, according to the United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture, which tracks threatened indigenous languages. It lists Cherokee in North Carolina as “severely endangered.”

2/27/23, 4:04 PM Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language - WSJ

“No one under 50 is fluent in Cherokee anymore,” said Roy Boney Jr., manager of

the Cherokee Language Program for the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, where he estimates roughly 3,000 out of about 325,000 Cherokee are fluent. A range of tactics, including Cherokee immersion schools, free language classes for adults, online videos and cellphone apps, haven’t reversed the decline in Cherokee, he said. “We’re at a juncture where if we don’t do something drastically different, it will fade out,” he said.

Something different might be happening at the house in the Great Smoky Mountains. Students, aged 19 to 68, who met at their teacher’s home on a recent night, spoke haltingly in the undulating lilt of Cherokee.

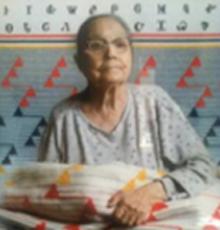

Barbara Duncan teaches Cherokee syllables to her class on Jan. 12 at her home in Whittier, N.C. Only about 200 people now speak Cherokee in North Carolina, and Barbara has launched language classes in hopes of preserving the ancient tongue. While some are enthusiastic about her e orts, other scholars and tribal leaders question whether she will succeed.

PHOTO: SUSANNAH KAY FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

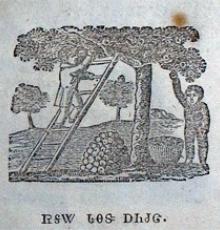

Teacher Barbara Duncan slotted colored pieces of paper into pockets on a cloth display to show the breakdowns of various Cherokee words, with the root and various prefixes and suffixes. The Cherokee language is so complicated that one word can form an entire sentence, and that prefixes and suffixes convey who, what and where something is taking place.

Because the variations can run into the tens of thousands, simple memorization won’t work. “It’s just too many big, long words to cram into your head,” she said. Her answer: Parse the words so that students can better understand where specific prefixes and suffixes go.

2/27/23, 4:04 PM Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language - WSJ

Ms. Duncan, who is 63 and the education director for the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in the town of Cherokee, said she has struggled for 20 years to try to become fluent in the language. Although she isn’t a Cherokee herself, she developed the educational program “Your Grandmother’s Cherokee,” together

with John Standingdeer Jr., 59, a Cherokee land surveyor who can only speak a few words of the language.

After nine years of personal research, the two say they figured out patterns in the word structure of the language, despite no formal linguistic training. They patented software to serve as a learning tool, began offering online classes and are planning to host an institute this summer at a nearby university so other tribes can use their methods.

Mr. Standingdeer said their approach arose from frustration with academic efforts to revive the language that have spent lots of money, but have produced few speakers. “If their methods were so good, why do we keep losing the language?” he said.

A poster detailing the Cherokee syllabary is photographed on Jan. 12 in Whittier, N.C. Each symbol represents a syllable rather than a single phoneme. Only about 200 people now speak Cherokee in North Carolina, and Barbara Duncan has launched language classes in hopes of preserving the ancient tongue.

PHOTO: SUSANNAH KAY FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Cherokee experts disagree on whether the effort to revive the language will have any impact. Some language professors see their new method as poorly conceived, an approach that could lure students into thinking Cherokee is easy, when it demands hard work. “I don’t think the program will do anything to increase the number

of Cherokee speakers,” said Hartwell Francis, the director of the Cherokee language program at Western Carolina University.

2/27/23, 4:04 PM Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language - WSJ

Brad Montgomery-Anderson, a professor who teaches Cherokee at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma, said that may be true, but “trying is better than nothing.” One big problem for teaching the language is that no one has developed an accepted curriculum, he said. Many languages have widely accepted textbooks, computer software and teacher-certification programs to make teaching easier and more coordinated, but “Cherokee doesn’t have any of that,” he said.

In North Carolina, millions of non-Cherokee tourists come to the area every year, many to visit the reservation’s casino—which has provided much needed cash for the tribe but has also hastened acculturation. In downtown Cherokee, the main town of the tribe’s reservation, most signs are in English, and many people working in Native American-themed tourist shops are not Cherokee.

Gilliam Jackson, 64, a fluent Cherokee, said that when he was younger, ministers preached in Cherokee and choirs sang in the language. He even remembers dreaming in the language—which he no longer does, he said.

Many Cherokee only speak a few words of greeting and perhaps some nouns, such as the names of animals or colors, he said. A few can hold a conversation, but only in the present tense. He thinks the amateurs’ idea of teaching Cherokee is a noble effort, yet he worries it is merely a desperate move.

“It’s definitely, in my opinion, going to be a dead language,” he said.

Students Kristy Maney Herron, left, and Tyra Maney, go over their Cherokee language work sheets on Jan. 12, in Whittier, N.C. Only about 200 people now speak Cherokee in North Carolina out of about 14,000 Cherokee in the state.

PHOTO: SUSANNAH KAY FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

2/27/23, 4:04 PM Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language - WSJ

Cherokee Look for Ways to Save Their Dying Language

By Cameron McWhirter | Photography by Susannah Kay Feb. 29, 2016 1:59 pm ET